Trump, Q, Deplorable, WWG1WGA, God wins, Save the CHILDREN!

Your info is fascinating. Could you make one post and explain it further?

🙂

Magnetogenetics refers to a biological technique that involves the use of magnetic fields to remotely control cell activity.

In most cases, magnetic stimulation is transformed into either force (magneto-mechanical genetics) or heat (magneto-thermal genetics), which depends on the applied magnetic field.

Therefore, cells are usually genetically modified to express ion channels that are either mechanically or thermally gated.

As such, magnetogenetics is a cellular modulation method that uses a combination of techniques from magnetism and genetics to control activities of individual cells in living tissue – even within freely moving animals.

This technique is comparable to optogenetics, which is the manipulation of cell behavior using light. In magnetogenetics, magnetic stimulation is used instead of light, a characteristic that allows for a less invasive, less toxic, and wireless modulation of cell activity.

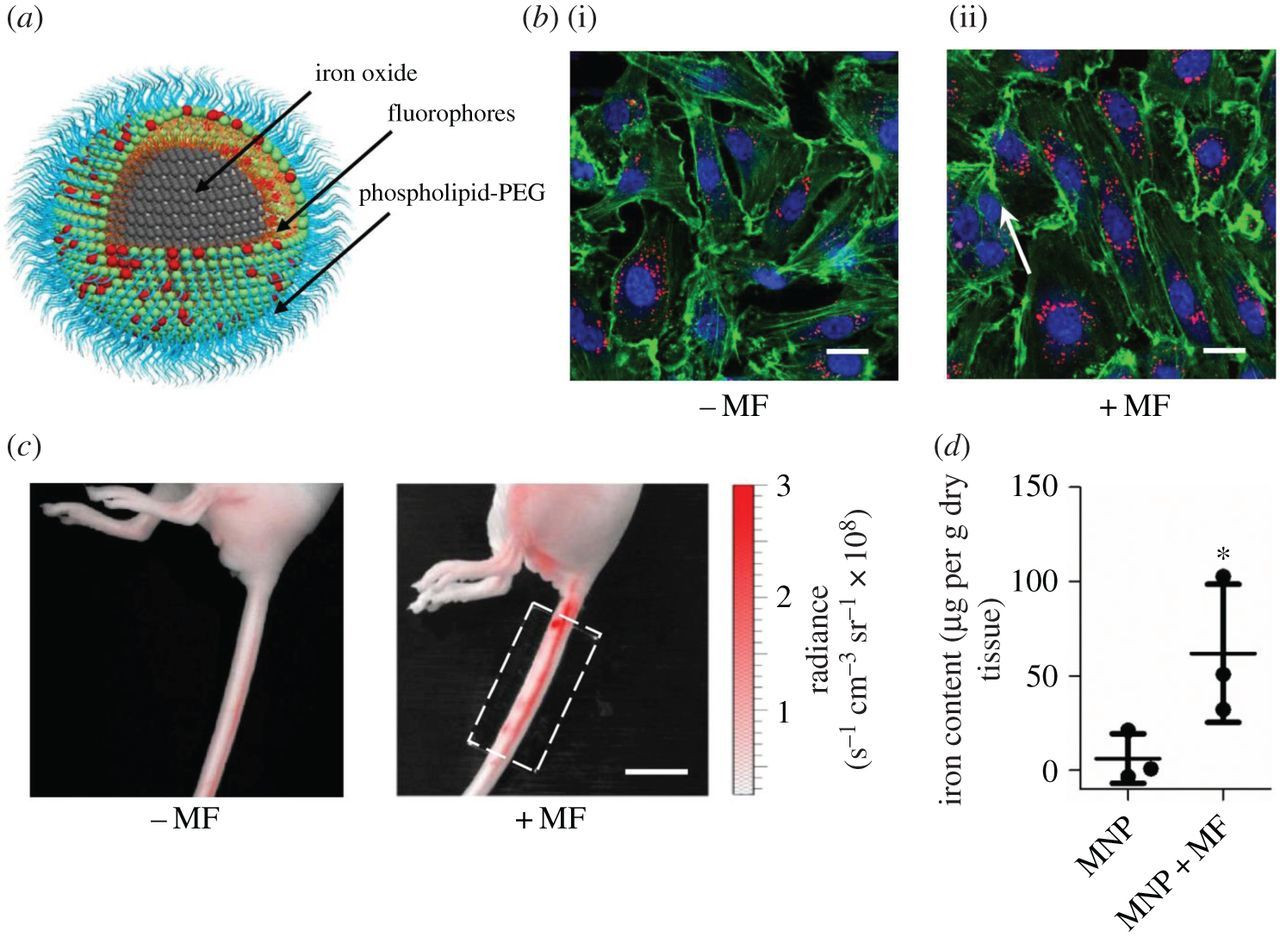

Iron oxide (Fe₃O₄) nanoparticles (IONPs) have received much attention for their utility in biomedical applications such as magnetic resonance imaging, drug delivery and hyperthermia.

Recent studies reported that IONPs induced cytotoxicity in mammalian cells.

However, little is known about the genotoxicity of IONPs following exposure to human cells. In this study, we investigated the cytotoxicity, oxidative stress and genotoxicity of IONPs in two human cell lines; skin epithelial A431 and lung epithelial A549. Prepared IONPs were polygonal in shape with a smooth surface and had an average diameter of 25 nm.

IONPs (25-100 μg/ml) induced dose-dependent cytotoxicity in both types of cells, which was demonstrated by cell viability (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazoliumbromide) and lactate dehydrogenase leakage assays. IONPs were also found to induce oxidative stress in a dose-dependent manner, evident by depletion of glutathione and induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation.

Comet assay revealed that level of DNA damage was higher with concentration of IONPs in both types of cells. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis showed that following the exposure of cells to IONPs, the expression levels of mRNA of caspase-3 and caspase-9 genes were higher.

We also observed the higher activity of caspase-3 and caspase-9 enzymes in IONPs treated cells. Moreover, western blot analysis showed that protein expression level of cleaved caspase-3 was up-regulated by IONPs in both types of cells. Taken together, our data demonstrates that IONPs have potential to induce genotoxicity in A431 and A549 cells, which is likely to be mediated through ROS generation and oxidative stress. This study suggests that genotoxic effects of IONPs should be further investigated at in vivo level.

The development of genetic technologies that can modulate cellular processes has greatly contributed to biological research. A representative example is the development of optogenetics, which is a neuromodulation tool kit that involves light-sensitive proteins such as opsins. This progress provided the grounds for a breakthrough in linking the causal relationship between neuronal activity and behavioral outcome.

The foremost strength of the genetic toolkits used in neuromodulation is that it can provide either spatially or temporally, or both, precise modulation of the brain nervous system.

To date, several technologies are adapted with genetics (e.g. optogenetics, chemogenetics, etc.), and each technology has strengths and limits. For example, optogenetics has advantages in that it can provide temporally and spatially precise manipulation of neurons. On the other hand, it involves light stimulation, which cannot penetrate tissues effectively and requires implanted optical devices, limiting its applications for in vivo live animal studies.

Techniques that rely on the magnetic control of cellular process are relatively new. This technique may provide an approach that does not require implantation of invasive electrodes or optical devices. This method will allow penetration in to the deeper region of the brain, and may have lower response latency.

In 1980, Young and colleagues have shown that magnetic fields with magnitudes in millitesla range are able to penetrate into the brain without attenuation of the signal or side effects because of the negligible magnetic susceptibility and low conductivity of biological tissue. Early attempts to manipulate electrical signaling within brain using magnetic fields was performed by Baker et al., who later developed devices for transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) in 1985.

To apply magnetogenetics in biological and neuroscientific research, fusing TRPV class receptors with a paramagnetic protein (typically ferritin) was suggested. These paramagnetic proteins, which typically contain iron or have iron-containing cofactors, are then magnetically stimulated.